The regimen paroeciae in a Time of Shortage of Priests

A Theoretical Legal Background for the Interpretation of Can. 517 § 2

By Elmar Maria Morein

English translation by Dr. Monica-Elena Herghelegiu, Tübingen.

Preface |

|||||

|

This essay has already been presented before an informed audience. The publishing rights of this essay are held by its author. The informed reader will certainly notice that the ideas presented in this paper are original and have not been presented in this way in the science of canon law. This is why I quoted in this essay just a limited number of canonical titles. Further literature will be added to the text in a future revised version intended for publication in an academic journal. I thank Prof. Dr. R. Puza for accepting this approach (modus operandi) to my academic research. |

1 |

||||

|

The General Administration Law and the Administration Studies as taught in Germany provide a legal basis which assists in understanding constitutional statements from the CIC and the cann. 515-552. It is therefore important to focus on them from an academic and interdisciplinary perspective. |

2 |

||||

|

Those who do so will recognize that the ecclesiastical legislator is aware of various models of regimen paroeciae. She or he will also understand why can. 517 § 2 can be developed in the proposed manner. |

3 |

||||

Part A of this essay will primarily focus on reflections concerning the General Administration Law. In part B these reflections will be applied on the basic model of the regimen paroeciae in the CIC. Part C is dedicated to reflecting the way in which the regimen paroeciae can be organized at a time when there is a shortage of priests respecting this legal background. |

4 |

||||

|

Whenever there is a reference to a canon from the CIC 1917 the abbreviation can. will be marked with an asterisk like *can. Some of the canons are subdivided in subsets. The reference to a certain subset will be indicated by the abbreviation ss. This will enable the division of a canon into more subsets. The common division in half-clauses implies that a clause can only have two subsets. |

5 |

||||

|

|

|||||

A. The Doctrine Viewed Especially On the Background of the General Administration Law |

|||||

|

On the basis of the concept of the General Administration Law, the legislator erects an office for a juridical person, for example a corporation. This office is designed to deal with a specific sphere of activities and includes various positions which are part of a well-determined hierarchy. The legislator develops institutions of the responsible body for administration issues (Verwaltungsträger) to enable it to act. (For the fluency of the text, the term responsible body for administration issues will be referred to as administration.)1 |

6 |

||||

|

|

|||||

I. The Responsible Body for Administrative Issues (the Administration) |

|||||

|

The Responsible Body for administrative issues is a legal institution which not only has the capacity to act (legal capacity) but is also a subject of rights and duties. Both physical and juridical persons and the corporate bodies possess these attributes. Whoever possesses a legal capacity or a legal personality can obtain financial support and has the right to be employed. |

7 |

||||

|

Whereas there are originary administrative bodies i.e. juridical persons which exist inderivative from any institution and possess originary power to act, there are also derivative administrative bodies, whose existence and duties are determined by the originary administrative body. |

8 |

||||

|

The state is an example of an originary administrative body irrespective of its function as a federation or as a country. An example of a derivative corporate body is the county or the local authority districts. These are self-reliant and self-managing although they are subject to the laws and the supervision of the state. They have territorial sovereignty. Through their directly-democratically elected representatives they have the ability and the authority to make their own decisions in a spirit of democracy. They support the state in carrying out its duties. |

9 |

||||

|

When the state itself performs its duties, i.e. through its institutions we describe this as direct administration by the state. If the state performs these duties by means of other independent administrations and their institutions, we may describe this as an indirect public (state) administration. Basically this indicates always the finality of the institution of law administration. The finality is concretized by the responsibilities assigned to the administration. |

10 |

||||

|

Whether it involves a federation, a country, a county or a local authority district, all are considered to be main levels carrying out the duties of the state. The legislator assigns them responsibilities through legal proposition. The duties of an administration are also called competences. In order to perform its duties the administration may need special authorizations to execute juridical action upon a third party. |

11 |

||||

|

|

|||||

II. The Responsible Body and its Administrators |

|||||

|

An administration has a legal capacity but it is not capable of acting. Other institutions are designed to complete the capability of acting. These institutions carry out the responsibilities (rights and obligations) assigned to the administration by the legislator. |

12 |

||||

|

Seen from this background institutions are always a part of the administration. They perceive the responsibilities of the administration not as their own but as alien / outside responsibilities. Institutions have to be examined from a double perspective: from the perspective of perceiving of tasks and from the point of view of forming the will of the administration. |

13 |

||||

|

An administration consists of several institutions which share responsibilities. The local authority district has inter alia a representative and a representation institution, the local council and the mayor. These are administrators of each institution and perform the responsibilities assigned to that institution. The first institution has a governing position while the other institution represents the members of the administration in social and legal issues. Institutions should be differentiated by their administrators, the concrete acting persons i.e. between the members of the local council on the one hand and the factual mayor on the other hand. Their action and their decisions are attributed to the respective administration as if it were its own action and its own decision. |

14 |

||||

|

|

|||||

III. The Public Authority as an Institution and the Employees of the Administration |

|||||

|

The public authority is also an institution of the administration. Actions of the administration are performed through it. The public authority sets itself apart from the already mentioned administrative organs because its staff is called by legal science not administrators but employees. They accomplish herewith clearly defined duties and are empowered with special authorizations to act outside the administration (as a kind of public relations activity) and vis-à-vis to members of the administration. |

15 |

||||

|

The office of a non-governmental public authority carries out inter alia the duties of the governmental administration. This makes clear that public authorities are institutions with a clearly defined position within the hierarchy of the governmental administrations. They are also executive authorities of governmental and non-governmental administrations. |

16 |

||||

|

A characteristic of the public authority is its bureaucratic aspect. This includes material resources such as real estate and working equipment and human resources i.e. the employees of the juristic person. Therefore, when considering this bureaucratic aspect the public authority is to be perceived as a well-ordered entity made up of human and material resources meant to fulfill clearly-defined tasks and enforced with clearly-defined delimited powers (authorizations) in the name of the administration. |

17 |

||||

|

Because the public authority is part of the administration, the latter is responsible for acquisition of the necessary material resources and also for the remuneration of its employees. |

18 |

||||

By meeting all these requirements the legal capacity of the administration is complete. Through possessing a legal capacity an institution is authorized to hire employees and so it also becomes a financial body. Possession of its own budget and its own staff are essential for an administration. |

19 |

||||

|

In the naming of the public authorities monocratic anachronisms have been preserved. It is common for the public authorities to be identified by the name of their leader. People talk about the mayor's office or about the district office but are meaning in fact the administration office of the commune or of the district which are headed by the mayor or the district chief executive. According to J. Ipsen these anachronisms are inappropriate. By using them one gains the false impression that the head of a certain public institution is omnipotent, omnipresent and omni-competent. |

20 |

||||

|

The continuing usage of such anachronisms does not reflect the modern system of distribution of work in administrational institutions2 because the employees of public authorities are independent and self-responsible in carrying out their tasks. |

21 |

||||

|

The leader of a public institution is not responsible for all the activities done in that institution. Nor is he directly in charge of official tasks. His specific rights and obligations differ from those of his colleagues. He is in charge with the management of the institution and it is his responsibility to ensure that all the tasks assigned to the public authority by the legislator are performed in an appropriate and target-oriented manner. In addition he can contribute with innovations or accept innovative ideas proposed by his colleagues. |

22 |

||||

|

If we transfer these aspects to the level of the local authority we can recognize that the mayor is the administrator of the representational institutions and leader of the mayor's office (Bürgermeisteramt), colloquially called the town hall. He is also a member of the local council (another representational institution). |

23 |

||||

|

|

|||||

IV. The Legal Institute Called Office |

|||||

1. The Definition of the Concept Office |

|||||

|

The office is an institution of law. Every office is founded and erected, i.e. it comes into existence within the framework of an administration. The office does not obtain legal personality by its mere erection. Only the administration can obtain this status for an office the act of entailment. |

24 |

||||

|

The office exists as long as the administration to which it is related. It is explicitly dissolved by the legislator when the corresponding administration has been dissolved. Its unlimited existence and evolution are determined by the existence and the evolution of the administration. |

25 |

||||

|

Because it is based on the administration, the activity of the office is determined according to the plans of the administration and by the extraordinary authorities needed by this institution. The role of the office is also determined by another institution of law: the position. Due to this, the office is a remarkable issue of legal organization. |

26 |

||||

|

There is a difference between an abstract and a concrete office. The concept of abstract office refers to the office itself related to an abstract, so to say to an administration. The concept of a concrete office is also related to a specific administration such as the government or the district local authority. Its sphere of activity is specified, its authority is eventually extraordinary and it incorporates concrete positions. The statements related to the office are summarized in the law of the offices. The criteria for this legal institute will be further emphasized by words or a text written in italics. |

27 |

||||

|

To make things clearer, I want to specify that the concept of office is used in legal terminology in plurisemantic contexts. When used in a legal administration terminology it has the meaning field of activity. The identification of the office as an institution of law underlines the view of the author of this essay. This view was also presented in more details in the doctoral thesis of the same author. In this thesis the legal institute office is understood as a juridical entity, "characterized on the one hand by specific criteria and on the other hand by a concrete purpose"3. The criteria are presented in the preceding chapters and the aim is determined by the responsibility of the administration. |

28 |

||||

|

|

|||||

2. Criteria for the Legislation of an Office |

|||||

|

The legal criteria for interpreting the term office as an institution of law can be established by analyzing the verbs and nouns by which the legislator designates the field of activity of the office, possibly enforces it with special authority and creates the necessary positions within this institution. However the office can be modified or even dissolved. |

29 |

||||

|

The point of reference for the institution of law called office is the administration on which an office is to be founded. |

30 |

||||

|

The existence of the office depends on the continued existence of the administration. |

31 |

||||

|

The office must have a leader. This post is held by someone occupying a leading position within the office. He / she is responsible for ensuring that the tasks legally assigned to the institutions are carried out. These should be fulfilled perfectly and goal-oriented with respect to the regulations of law. |

32 |

||||

|

Within an office, there are various legal positions which are regulated by the hierarchy of positions. |

33 |

||||

|

|

|||||

V. The Position as Institution of Law |

|||||

1. Definition of the Concept Position |

|||||

|

The position is an institution of law as is the administration and the office. Since it is established by the administration, this office is regulated by it concerning its sphere of activity on the one hand and the positions distributed to it on the other. |

34 |

||||

|

In contrast to the office which is a matter of legal organization, the position is a matter of the services of public law. In the same way in which we differentiated between the concrete and the abstract offices we can make distinctions within the concept position. The positions can be abstract or concrete. |

35 |

||||

|

The positions can be further distinguished as basic or special (not basic) ones. The basic positions are mandatory for the existence of the office and for the ability of the administration to act. The non-basic positions are those which can be activated only for a certain period of time. |

36 |

||||

|

All positions are ordered within a hierarchy headed by the managing position and completed by the non-managing positions which may also have managing competences. |

37 |

||||

|

Depending on the size of the public authority there are various levels of management. The leading person as manager of the public authority or as manager of the administration is responsible for supervisory control and for the supervision of the activity. He (or she) gives instructions to his (or her) colleagues. The colleagues with whom he maintains a more intensive collaboration are the heads of the departments. These are responsible for the supervision of their colleagues. This aspect is maintained at each level of the hierarchal ladder. |

38 |

||||

|

The superior always has priority in professional supervisions. It is clear that the job hierarchy incorporates a legal status (the job hierarchy is associated to the legal status) within the office. Supervision of the activity is exclusively the responsibility of the manager of the public authority. |

39 |

||||

|

This position is normally advertised with a presentation of its requirements and its classification. One of the applicants obtains the post. He / she now becomes an employee with the rights and obligations associated with that position. In certain circumstances he / she is given special authorization to carry out tasks associated with the position. Due to his / her position he / she has the right to act as legally relevant vis-à-vis a third party. |

40 |

||||

|

The regular authorizations are to be understood as licenses which enable the employee to perform the tasks associated with his position and eventually empower him with special authorizations associated with these tasks. |

41 |

||||

|

The process of advertising a position ends when the chosen candidate accepts it. In doing so he / she acknowledges a commitment to conscientiously fulfill the duties associated with the position. |

42 |

||||

|

The field of activity of an employee (ad personam) is shaped even before his employment. It is already specified in the workplace description. This means that the job description and the job specification can differ from each other. The job specification may be reduced to such an extent that all the tasks associated with the position could be fulfilled by a single person. The field of activities corresponding to a position differs from the sphere of activity assigned to an office but actually the latter includes the first one. The sphere of activity assigned to an office is wider as it has been designed for an administration. |

43 |

||||

|

As a consequence, the employee is not an office holder although he is part of the office along with all the others holding positions, but an office bearer. In performing their tasks the position holders enable the office to function. They fulfill their tasks in the office with regard to the administration on which the legislator founded the office (with its sphere of activity and the incorporated positions). For their part, the position holders fulfill their office tasks to a great extent with the public authorities. |

44 |

||||

|

Office tasks may also be fulfilled outside a public authority. An example is the case where completion of a task requires a meeting with experts on the ground - meaning outside the public authority. |

45 |

||||

|

The application process described above is not mandatory. There are positions which can be filled without it. In such a case, the candidate becomes a position holder. |

46 |

||||

|

By holding a position - for example a managing position - one may enjoy a special social status within the group on which the legislator has founded the office or within the public authority. It is important to mention this because the use of outdated designations of the public authorities may lead to the impression that the mayor is responsible for all the duties and that other employees are performing tasks for him personally and not tasks which have been delegated by him. This is how things were perceived in former times. |

47 |

||||

|

By accepting the paradigm shift and by becoming aware of the division of the working process within the administration, we realize that the mayor, as manager of a public authority and as holder of a managing position within a local office has different tasks and responsibilities. This aspect should be understood by the members of the administration as well as by the employees of a public authority. |

48 |

||||

|

The extent to which social status depends on the fact that the leader of a public authority of a derivative administration is usually also the administrator of the representative institution in matters of legal and social matters is not significant for this context. |

49 |

||||

|

Let us turn our attention to the leading position within the office. Its holder is not only the manager of the public authority but also the manager of the representative institution and implicitly a member of it (as holder of the managing position within the office). As an administrator of the representative institution, he must always fulfill his tasks in accordance with the actual legislation. |

50 |

||||

As a conclusion, the holder of the managing position is also responsible for the management of the office. |

51 |

||||

However, positions can eventually be lost - for example when positions are cancelled due to financial shortages. By losing a position, one also loses the right to act in the name of the administration or vis-à-vis its members. If this position is not cancelled after the departure of the former employee, then it remains vacant. |

52 |

||||

|

All the statements referring to positions are contained within the legislation of positions. Its criteria will be marked by italics within the following text. |

53 |

||||

|

|

|||||

2. Criteria Concerning the Legislation of the Positions |

|||||

|

The legal terminology revealing the criteria designing the position as an institution of law consists of verbs and nouns, by means of which a position is being established within an office and assigned to a physical person. All the facts expressing a different procedure of gaining a position, as well as all the facts expressing the loss of a position are to be taken into consideration. If somebody loses his position but the post is not cancelled, we call it a vacant position which can be occupied again. |

54 |

||||

|

The office is the point of reference for a position. The position has been created within the office to enable the administration to act through the position holders and be able to carry out its tasks vis-à-vis its members. |

55 |

||||

|

The durability of the position can vary. Considering the basic positions, including the managing position, they continue as long as the office continues to operate. As for positions which have been authorized only for a certain period of time, they can end their activity sooner. |

56 |

||||

|

According to the hierarchy of the positions there is the managing position and many non-managing positions which can also have leading competences. The non-managing positions may also be related to each other according to a different hierarchy. Each place within the hierarchy corresponds to a legal status within the office. |

57 |

||||

|

The holder of the managing position within an office is also the administrator of the representative institution and due to this function he legally and socially represents the administration before the public. Implicitly, he is a member of the representative institution and manager of the public authority. And, of course, he is responsible for leading the office. |

58 |

||||

|

The legislator establishes the sphere of activity, the responsibilities and the special authorities of the office by legal rules. These serve as a base for the competences and the authority of the administration and create a working place description for a possible candidate who is chosen to fulfill all the requirements. |

59 |

||||

All the position holders are employees of the administration. The latter is responsible for the payroll, for providing the workspaces and the work equipment. |

60 |

||||

|

|

|||||

VI. The Sphere of Activity Specified by the Legislator |

|||||

|

The sphere of activity is not an institution of law, unlike the administration, the office and the position. Each institution of law is defined by various elements and by a specific finality. We mentioned earlier the various elements corresponding to each institution of law, the finality is mentioned concretely by the duties of the office. The office, however, is concretely indicated by the sphere of activity. |

61 |

||||

|

If a special authorization is needed to perform certain tasks of the office and to fulfill legally relevant duties vis-à-vis a third party, this must be designated by the legislator in a positive legal sense, together with the tasks assigned to the office. This is to be done with regard to the administration as it is its competence. The office tasks assigned by legislation are to be considered mandatory by the administration. |

62 |

||||

|

The responsibilities of the administration within the institutions mentioned above are accepted by the administrators and by the position holders: that means, by the employees of the administration. The members of the administration may contribute as volunteers to carry out the duties. However they are required to respect the legislation. |

63 |

||||

|

Should the tasks of the office be systematized under the supervision of the manager, one of the methods can be the division of tasks. This method is taken from the field of the Administration Studies which should not be confused with the General Administration Law. According to this method, tasks are to be objectively categorized in bundles according to their similarity. Each bundle can be further subdivided according to similarities. |

64 |

||||

|

The task division can possibly further be subdivided. It is a constitutional component of the position and it is also mentioned in the plan of work division within the administration. One should always check whether a special authorization is necessary in order to carry out the office tasks mentioned. |

65 |

||||

|

The work division method is meant to enable a quick overview of the tasks. Another method is the division of the office tasks according to their relations to each other. By adopting this method the tasks are divided into the subcategories: departmental tasks and interdepartmental / cross-sectional tasks. |

66 |

||||

|

The departmental tasks are those tasks which directly affect the segments of economy, education, sports and culture. |

67 |

||||

|

The interdepartmental tasks are those which precede the departmental tasks, being necessary for the fulfillment of the latter. Such tasks refer to financial questions, to personnel and means of organization but also to legal activities. |

68 |

||||

|

Similar departmental and interdepartmental tasks can be bundled in departmental and interdepartmental units. |

69 |

||||

|

By dividing the office tasks according to the criterion relationship of the duties of the office to one another, there is one other category to add to the previously-mentioned units: we are referring to the Operating Services. These include the typing, the registry, the courier services, and the library. These services can only be carried out by using the results obtained by the interdepartmental tasks. As an example of this we point to the library which can function only after financial support has been guaranteed. |

70 |

||||

|

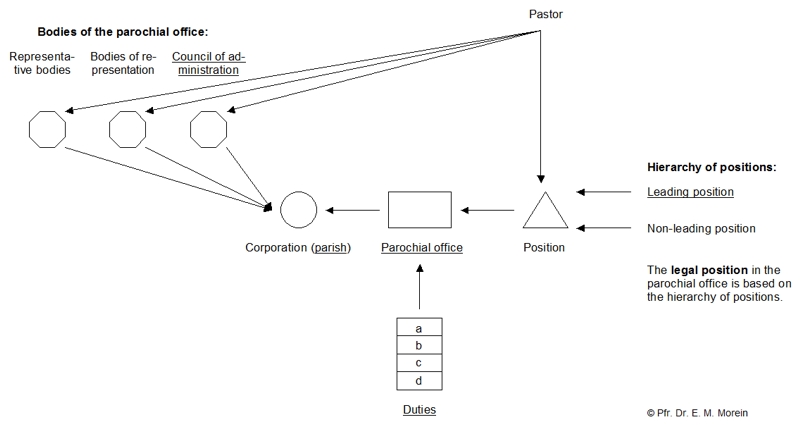

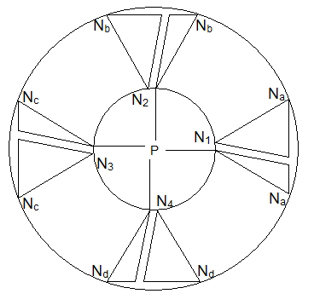

The scheme below expresses the ideas which have already been presented. It exemplifies the structure on the municipal level, leaving out details referring to separate spheres of activity. This should also clarify the way of thinking adopted by the administration. |

71 |

||||

Graph 1: The legal doctrine viewed especially on the background of the general administration law |

72 |

||||

|

|

|||||

B. The Transfer of Juridical Terminology on the Canonistic Terminology of the Codex Iuris Canonici 1983 |

|||||

|

The ideas emerging from the civil administrative law represent a new basis of legal theory. With their help we can interpret the statements on constitutional law made by the universal ecclesiastical legislator. One is particularly interested in the consequences of applying this new legal theory to the interpretation of the cann. 515-552 and the concepts paroecia and diocesis and their associated canons. |

73 |

||||

|

The recipient of this interpretational transfer is expected to be open to a new way of thinking and to leave behind the usual interpretation of these concepts. |

74 |

||||

In applying this transfer I assumed that the legislator had a background in legal administration in mind when he formulated the canons of constitutional law in the Codex Iuris Canonici.4 |

75 |

||||

|

The legal concept office was practically unknown to the canonists until the CIC was promulgated in 1983. This does not imply that the ecclesiastical legislator excluded it from its theoretical assumption or excluded concepts of administrative law when formulating the new canons. |

76 |

||||

|

In German theology one can differentiate three meanings of the word office: a) the dogmatic meaning in the sense of ordo signifying the sacramental consecration, b) the canonistic meaning of position and c) the legal meaning in the sense of a legal institute. |

77 |

||||

|

Because of this variety of possibilities of understanding the German concept office (Amt) we will use in this paper the concept office only when we refer to the legal institute. When we refer to the office from a dogmatic perspective we will use the term sacramental ordination and when we refer to the canonistic meaning we will use the concept position. K. Mörsdorf differentiated between a main and a secondary office. This should be the same as when I differentiate between a leading position and a non-leading position in the parish when talking about a position in this paper. |

78 |

||||

|

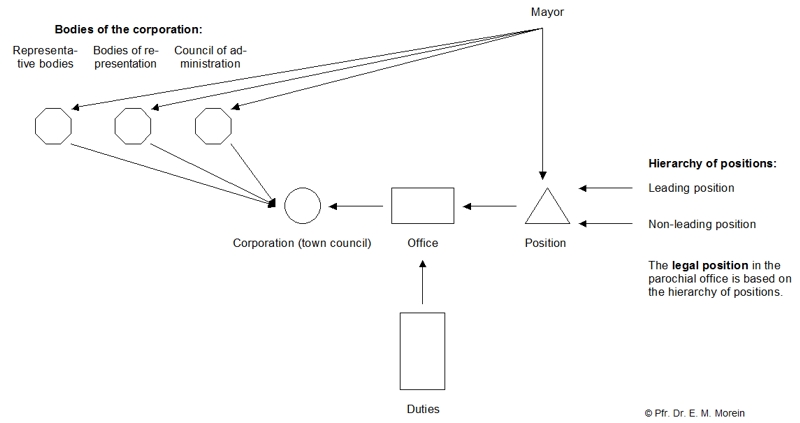

By transferring legal concepts on to the codicary concepts in certain canons the diversified use of the concept paroecia by the ecclesiastical legislator becomes even clearer. The German concepts for which the legislator uses the concepts paroecia and paroecialis are underlined in graph 2. The graph also contains a differentiated plan of pastoral duties which are listed under the concept cura pastoralis. |

79 |

||||

|

|

|||||

I. Significance of the Concept paroecia in the CIC |

|||||

|

The legislator uses the concept paroecia in can. 515 in a variety of meanings. One should mention the meaning parish which obtains the status of a legal personality through its erection according to can. 515 § 3. As such the parish is a responsible body of property and assets. The legislator speaks about this in can. 532, subset 2, when he mentions the bona paroeciae. The ecclesiastical legislator differentiates according to can. 518 between the parish as a regional and as a personal corporation. This is the postconciliar meaning of the concept paroecia in CIC. |

80 |

||||

|

The parish as a corporation is not able to perform activities on its own. Therefore it needs bodies to lead this corporation, according to the stipulations of the ecclesiastical legislator. |

81 |

||||

|

He names two representative bodies for these activities, one in can. 536 and the other one in can. 537. According to the stipulation of the CIC both have an advisory role. In both of them the priest has a leading position, because he holds the leading position in the parish administration. According to can. 536 the legislator of the particular church has an obligation to organise the administration of these bodies. According to can. 537 the administrative council for finances must be established as a body of the parish. Only the organisatorical scheme of this body is presented in graph 2. |

82 |

||||

The legislator also understands the pastor as being the administrator of the representative bodies as in can.. 532, subset 1. It is his duty to represent the parish in legal matters. |

83 |

||||

|

The legislator considers the body to be a council of administration (Behörde) as it is described in can. 535. If one follows the inner logic of this organizational scheme one has to translate the concept paroecia and the adjective paroecialis with the concept administration (Behörde) or with the adjective administrative (zur Behörde der Pfarrei gehörend). We could identify the same meaning of paroecialis already in *can. 470. |

84 |

||||

|

For the parish to be erected, suppressed or altered according to can. 515 § 2, the legislator establishes a parochial office according to the same canon. The concept paroecia can be understood in its double meaning in this canon: paroecia as parish and also as parochial office which can be altered by the diocesan bishop like the parish. |

85 |

||||

|

Usually one interprets can. 515 § 2 according to its postconciliar meaning - as if the legislator thinks in this canon of the parish only as a corporation. |

86 |

||||

|

The three verbs I mentioned above - erigere, supprimere and innovare - are also used in can. 148, subset 1, when the legislator talks about the erection, supression and altering of an office.5 Because of an inner logic of legal terminology one has to assume that the legislator is not only referring to the corporation parish but also to the parochial office when he uses the concept paroecia. |

87 |

||||

|

The canonist H. Socha also notes in his commentary (MK-CIC 148, note 2) that these three verbs which describe an organizational task are also used in can. 515 § 2.6 |

88 |

||||

The legislator also talks about the governance of a parish in can. 541 when using the concept regimen paroeciae. In can. 526 § 1 another synonym is used - cura paroeciae. According to R. Köstler one can translate the concept cura with governance.7 |

89 |

||||

The legislator does not speak in these canons of governance in the sense of postconciliar theology without the preconciliar background of the concept paroecia as in *can. 472, 2° and 3° or in *can. 460. Nor does the legislator speak in can. 533 § 3 about parish governance. He intends here to talk about the governance of the parochial office as it is understood from a pre- and postconciliar perspective. The criteria for the law of offices as they are named in Part A.IV.2 come into effect, so that the concept paroecia can be better described legally in both codices of the Latin Church. |

90 |

||||

|

The legislator assumes that there are a multitude of positions in the parochial office when he formulates can. 536 § 1, since he also talks about the pastor presiding over the pastoral council (officium in paroecia). The legislator also speaks in can. 521 § 3 about the officium parochi, which means that the pastor holds an office in the parish (officium in paroecia). |

91 |

||||

|

This office of the pastor has to be understood from a background of administrative law. The legislator offers the leading position in the pastoral office to a priest who, by the bestowment of this office, is a pastor according to can. 519, subset 1. |

92 |

||||

If this assumption is correct then the concept paroecia should be understood on the basis of legal vocabulary and criteria for bestowing legal positions. With its help any form of granting of position is expressed. In can. 519 and in the other canons in which the noun paroecia is used, the priest receives a leading position in the pastoral office (see also cann. 520 § 2, 1747 § 1, 1748). Only a position can be assigned; a corporation can never be assigned. |

93 |

||||

|

The legislator speaks in cann. 539 and 541 and also in cann. 1740, 1741 und 1751 about the loss or the vacancy in the leading position of the pastoral office from the point of view of criteria of legal concepts and administration of offices. |

94 |

||||

In all these canons the legislator uses the concept paroecia. It is clear that here it refers to the loss of a leading position in the pastoral office as was also mentioned in the preconciliar CIC (part A.V.2). This can be proven if one looks at the parallel canons in the old CIC and if one accepts the legal terminology. |

95 |

||||

|

It becomes clear to an attentive reader that the concept paroecia can have different meanings in the same canon depending on the point of view from which one looks at it: from the point of view of ecclesiastical positions or of ecclesiastical offices (see can. 541). The legislator focuses at times on the vacant leading position in the parochial offices and at other times on the leadership of the parish. |

96 |

||||

|

The legislator not only creates positions in the parochial office but also provides a circle of duties which are described in detail in cann. 528-537. |

97 |

||||

|

Because the ecclesiastical legislator describes the parochial duties as obligatory duties in these canons he must also name the duties for which one needs the sacramental consecration and those for which one needs only a facultas from the potestas regiminis, i.e. a special authorisation (facultas) out of the many extraordinary competences of the power of governance. |

98 |

||||

|

It is important to investigate this question. One can recognize that the sacramental consecration is only necessary in order to fulfill six duties: celebration of Eucharist (can. 900 § 1), spending the anointment (can. 1003 § 1), spending the sacrament of penance (can. 965) and spending of confirmation (can. 882). From the point of view of the universal legislator the diaconal and priestly consecration is also necessary for spending blessings and dedications (can. 1169)8 and for delivering the homily (can. 767 § 1). |

99 |

||||

|

If one analyses the terms sacerdos, presbyter and diaconus in the CIC from the perspective of the duties connected to these positions we come to the conclusion mentioned above. |

100 |

||||

|

In this case we are also obliged to conclude that the legislator connects the sacramental consecration with the fulfillment of certain duties. In his view the sacramental consecration is conferred so that the ordained priest can fulfill these duties on the level of the parish. |

101 |

||||

This view might provoke controversies, estrangement or refusal among theologians who are confronted with the fact that the legislator does not differentiate dogmatically between priest and parish. |

102 |

||||

|

Those who have a different opinion or believe that the legislator does not administer the sacramental consecration so that a priest can fulfill specific duties i.e. duties related to the sacramental life of the parish are free to hold their own opinion. But they must also prove that their argument is correct. |

103 |

||||

As long as the arguments of those who hold a different position are not convincing the postulate has to be verified according to which laypeople partake in the duties which are related to the sacramental consecration. |

104 |

||||

If the duties are conferred by the sacramental consecration, then the canons of the CIC in which the legislator names the duties of a parish are no longer needed and would be invalid. |

105 |

||||

|

The legislator demands for the completion of some duties not only the sacramental consecration but also a facultas of the potestas regiminis. |

106 |

||||

Every particular extraordinary authorisation is transmitted by the conferring of a position - as for instance the right of the priest to administer the sacrament of confirmation according to can. 883, 2°. |

107 |

||||

The assistant at a marriage is also required to have received a facultas of the potestas regiminis, but not the ordo, cf. can. 1111 together with can. 1112. Therefore this special facultas belonging to the potestas regiminis can also be granted to lay people through the conferring of a position. |

108 |

||||

|

This is the background according to which we can divide into four categories the pastoral duties which are specified by the legislator but are not conferred through sacramental ordination (otherwise the cann. 528-537 would be redundant): |

109 |

||||

|

110 |

||||

|

111 |

||||

|

112 |

||||

|

113 |

||||

|

Judging the facts against this total background one has to say that it is not correct to translate the term paroecia unequivocally in the fifth Latin-German translation of the CIC with the term parish (Pfarrei) and the adjective paroecialis with the term belonging to a parish (pfarrlich). The legislator envisages more than one legal reality when he uses the concept paroecia and its adjective. |

114 |

||||

|

In can. 526 § 1, subset 1 the legislator presents the fundamental model for a regimen paroeciae. It is presented in detail in the canons 515-552. According to this model the pastor can govern only one single parish (unius paroeciae tantum curam ... habeat). Nevertheless I believe one should translate the adjective paroecialis in this content as belonging to the leading position in the parochial office (zur Leitenden Stelle im Pfarramt gehörend) or corresponding to the leading position in the parochial office (die der Leitenden Stelle im Pfarramt entspricht). |

115 |

||||

|

The reflections which helped us to transfer the legal terminology of part A onto the codicary term paroecia can be summarized into 4 categories (a-d) taking into consideration the parochial duties as seen in Graph 2: |

116 |

||||

|

Graph 2: The view of the ecclesiastical legislator on the regimen paroeciae as described by can. 526 § 1, subset 1 |

117 |

||||

|

|

|||||

II. Description of the Term cura pastoralis |

|||||

|

With the help of legal terminology one can prove that the universal legislator uses the concept paroecia with different pre- and postconciliar meanings. We still have not proven that the universal legislator names with the term paroecia also the duties of the parochial office. From the point of view of civil administrative law one can divide these duties in different fields of activities and every field of activity in a subordinated field of activities, in scopes of duties and fields of functions. |

118 |

||||

|

In this article we cannot describe in detail the different fields of activity of the parochial duties, their intertwining and the scope of their functions. However working on the basis of the already described categories of an ecclesiastical plan of the fields of activities9 one can say that the legislator has envisaged in cann. 528-537 all the categories relevant for such a plan. |

119 |

||||

|

In the canons 528, 529 § 1, 530 and 534 we can read the apostolic main sections of proclamation, liturgy and charity, in the canons 531 und 532, subset 2 we find the non-apostolic cross-section of finances and in can. 535 we find the non apostolic registrar's office. That the parish is a derivative corporation becomes clear from its integration in the parish's predetermined originary juridical persons in can. 529 § 2. |

120 |

||||

|

The next important question is how to define the concept cura pastoralis within this broadly described plan of sets of activities. |

121 |

||||

|

The German speaking canonists have assumed in the tradition of Herbert Schmitz that all the duties of the parochial office are duties of the care of souls. He distinguishes between duties regarding the direct care of souls and duties regarding the indirect care of souls.10 However one can see that the statement of Schmitz cannot be sustained if one looks attentively at the plan of sets of activities and at the fact that the legislator describes with the concept cura animarum exclusively duties in the domains of proclamation and liturgy (compare cann. 757 and 771 § 2 on the one hand and cann. 922, 986 § 1, 1003 § 2 on the other hand). |

122 |

||||

|

H. Schmitz defines as duties of indirect care of souls the duties belonging to the non-apostolic domain. These are not duties concerned with the care of souls but are described by the legislator as duties belonging to the domain of proclamation or liturgy. |

123 |

||||

|

They are subsumed by the legislator in can 150 under the concept plena cura animarum and then merged into the set of duties called cura pastoralis. This set of duties contains the subsections of proclamation and liturgy. |

124 |

||||

In the German canonistic discussion it is not controversial whether the concepts plena cura animarum and cura pastoralis are synonyms. One is obliged to prove that these concepts are associated with offices which are not connected with the domains proclamation and liturgy, like the offices of juridical affairs mentioned in can. 532. Even though they belong to another domain H. Schmitz attaches them to the cura pastoralis.11 |

125 |

||||

|

This interpretation is important if we want to redesign the legal concept described in can. 517 § 2 (compare Part C). |

126 |

||||

One must still answer open questions such as: How does one understand the concept cura pastoralis paroeciae used in can. 517 § 2? The legislator substitutes this concept with a pronoun in can. 515 § 1, subset 2. |

127 |

||||

|

One could say that we must deal with a particular competence of the parochial office. But since the competences within the parish can be administered by administrators, moderators and also by the members of the corporation i.e. of the parochial office, the concept cura pastoralis paroeciae can only be understood in the sense that it has to do with the duties of the cura pastoralis which is described as being part of the circle of duties of the pastoral office. This interpretation is only possible by transmitting the content of legal terminology upon codicary language when we talk about the circle of duties of the parochial office. When the legislator uses the Latin term paroecia he refers to both the duties of the parochial office and to the parochial office as a corporation, i.e. to the content of the parochial office and to the subject parochial office. This is why we underlined in scheme 2 the term duties. The term cura pastoralis paroeciae has to be translated by domain of duties cura pastoralis of the parochial circle of duties (as distinguished from the domain of duties cura pastoralis dioecesis, i.e. the domain of duties cura pastoralis in the circle of duties of the Episcopal office, cf. can. 414). |

128 |

||||

|

None of the other duties belonging to the circle of duties of the parochial office as described in can. 517 § 2 needs to be moderated by a priest if we judge everything from a positivistic legal perspective. Thus at a time when there is a lack of priests we have the possibility to delegate a series of duties to persons who are not priests. These can be entrusted with the care of duties in parishes. The model which I present here cannot be found in the model of the regimen paroeciae as described by can. 526 § 1, subset 1. |

129 |

||||

|

In relation to the domain of duties described by the cura pastoralis one should emphasize that the pastor is in the basic model of the regimen paroeciae as a consecrated priest the leader of the parish, i.e. a pastor proprius according to can. 515 § 1, subset 2. |

130 |

||||

|

I should add two explanatory notes at this point. 1) Can. 528 § 1 has to be subsumed to the set of duties belonging to the proclamation of the word, and cann. 528 § 2, 530, 534 belong to the set of duties of the liturgical domain. The legislator of the universal church substantiates by these canons the domain of duties of the cura pastoralis (cf. cann. 515-552). |

131 |

||||

2) One notes the equivocality of the term paroecia in can. 515. The term can either mean parish (can. 515 § 1, subset 1, 515 §§ 2 und 3), or parochial office (can. 515 § 2) or circle of duties of the parochial office (can. 515 § 1, subset 2). |

132 |

||||

|

|

|||||

C. Significance of this Perspective for the Understanding of can. 517 § 2 |

|||||

|

The legislator stipulates in can. 517 § 2 that a pastor should be the moderator of the cura pastoralis. According to the same legal prescriptions one has to make a distinction between the fulfillment of the duties described in the cura pastoralis and the governing of the fulfillment of these parochial duties by people who are assigned for governing. |

133 |

||||

|

The other priest (aliquis sacerdos) in can. 517 § 2 is not exempted from his pastoral duties. He has to fulfill at least the six duties which are connected to his sacramental consecration. |

134 |

||||

|

Can 517 § 2 stipulates that when there is a lack of priests the diocesan bishop has to entrust the pastoral care (cura pastoralis) of the parish to a deacon or to another person who is not a priest, or to a community of persons, or he is obliged to appoint a priest who, provided with the powers and faculties of a pastor, is to direct the pastoral care. Based on a legal positive argumentation this means that a parish can be governed without problems by someone who is not a priest when the diocesan bishop notices a penuria sacerdotum. However the legal position of someone who is not a priest is different. |

135 |

||||

|

This conclusion has as a positive legal premise of the legislator the fact that in all other secondary domains of duties of the parochial office there is not a single duty which specifically requires a consecrated presbyter for its fulfillment. A person who is not a priest may only govern those domains which do not require sacramental consecration. If the legislator did not act in this way then someone who is not a presbyter could moderate the domains of the cura pastoralis. But someone who is not a presbyter cannot fulfill this duty. |

136 |

||||

|

If one can prove that a deaconal consecration is needed to fulfil the duties in any of these domains within the circle of duties of a parochial office, then this particular domain must be governed only by a deacon. |

137 |

||||

|

The CIC does not contain any indication that the deaconal consecration is necessary to fulfill any duties beyond the circle of duties of the circle of cura pastoralis. |

138 |

||||

At the same time the duties of the cura pastoralis cannot be fulfilled entirely by a deacon because the duties of pastoral care always include activities for which the priestly consecration is indispensable. |

139 |

||||

|

How can we justify from a theoretical and legal point of view this changed legal position of someone who is not a priest but leads a parish? |

140 |

||||

|

|

|||||

I. Altering of the Parochial Office |

|||||

|

We have already assumed that the legislator uses the term paroecia in can. 515 § 2 in a double meaning, since a parochial office has always to be erected for a parish. The parochial office will contain a certain number of positions necessary for the governing of a parish. These positions can not only be granted but can also be lost. |

141 |

||||

|

According to can. 515 § 2 a parish in the sense of a parochial office can be altered by a diocesan bishop. |

142 |

||||

This could be done by changing the duties of the parochial office. However this is not possible since it is not permitted by the universal legislator according to the stipulations of cann. 528-535. The diocesan bishop can only alter the duties which he himself imposed on a parochial office. |

143 |

||||

|

The diocesan bishop has another alternative. He could alter the governing position of the moderator in the parochial office by dividing it. A priest can be in charge with the duties of the cura pastoralis as described in can. 517 § 2 while someone who is not a priest may execute the duties of the cura pastoralis for whose execution no sacramental consecration is necessary and be put in charge of the domains of duties in each separate parish which do not contain any duty for which one does need priestly or deaconal sacramental consecration. |

144 |

||||

|

One may also think of another model. An aliquis sacerdos moderates the cura pastoralis, while a person who is not a priest governs certain duties of a parochial office. Each of them has a co-worker who is also not a priest. These co-workers who are not priests do not hold a divided leading position but a non-leading position in the parochial office and are attached to one of the two people who do possess the leading position in the parochial office from the point of view of employment law. |

145 |

||||

|

From the perspective of duties the leading position can be divided. |

146 |

||||

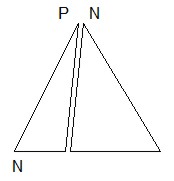

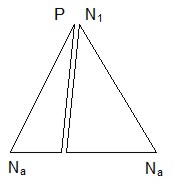

One can represent this division in a graph by splitting the triangle which symbolizes a position in two smaller triangles like in the following figures, if one does not want to draw a vertical line through the triangle which could imply that the position should be exactly cut in half which is not necessarily intended: |

147 |

||||

|

148 |

||||

The triangle as symbol for the positions in graphs 1 and 2 whose top symbolizes the one leading position and whose basis represents the many non-leading positions has become a pair of triangles in graphs 3 and 4. The smaller triangle to the left in each graph symbolizes only the divided leading position of the priest (P) with his possible co-worker (N or Na) within the cura pastoralis. The smaller triangle to the right represents only the divided leading position of the person who is not a priest (N or N1) who is either colleague and co-worker of the priest at the same time (graph 3) or is a colleague of the priest and has the same co-worker as the latter (Na in graph 4). This co-worker can work in all fields of duties of the parochial office. |

149 |

||||

The observer notes two points: To verify this hypothesis, on the one hand one has to analyse whether the criteria according to which some pastoral duties are granted to persons only on the basis of their sacramental consecration are mere dogmatic or mere canonistic criteria. On the other hand one has to analyse the legal position of a priest-moderator and the position of a person who is not a priest (N or Na) but assumes duties within a parochial office at times when there is a lack of priests. The legal position of these two actors has changed considerably in the sense that the priest moderator has lost some of the duties which were normally included in his function of governing and these duties have been assigned to the person who is not a priest. |

150 |

||||

|

If someone who is not a priest (permanent deacon or layperson) governs the domain of duties subsumed under bona paroeciae then he / she consequently has the right to vote in the finance council. If this person takes over the duties of the pastor as moderator then he / she should be authorized to sign documents, as prescribed by the concordates.12 |

151 |

||||

|

If someone who is not a priest possesses a divided leading position in the parochial office and performs a certain type of duties and is a co-worker of the pastor then he would hold at the same time a non-leading position in the parochial office in so far as the duties of the cura pastoralis are concerned. In this case the individual who is not a priest would have two different legal positions in the same parochial office. On the one hand he would be the colleague of the priest moderator and on the other hand his co-worker. |

152 |

||||

|

If one follows this thought through then the leading position in the parochial office is not vacant. This is not possible continuously before the background of can. 151, which stipulates that positions which are in connection with the care of souls are (therefore) to be assigned as fast as possible. Consequently can. 517 § 2 does not speak about this. The position is occupied by several people so that the leadership of the parish is ensured in this manner. |

153 |

||||

|

At the same time a non-leading position in the parochial office may be granted to someone who is not a priest but participates at the cura pastoralis. This person may have as a supervisor either a priest or a layperson. It is also possible that a layperson (non-priest) shares a split leading position in the parochial office while at the same time occupying a non-leading position in the parochial office as far as the cura pastoralis is concerned. |

154 |

||||

|

According to can. 151 the diocesan bishop is required to fill the positions entrusted with pastoral duties without prorogation. According to the same canon several other duties which do not belong to the cura animarum can be associated with this position. An officium bound with the cura animarum can also be a position connected among other things with the cura animarum. |

155 |

||||

|

|

|||||

II. Arguments for Dividing the Leading Position in the Parochial Office |

|||||

|

One may ask whether the division of a leading position in the parochial office is legally acceptable. |

156 |

||||

If we look at can. 152 we notice that the same person cannot hold different positions which are incompatible with each other. This does not refer to the non-leading positions in different pastoral offices i.e. on the same constitutional level, since a parochial vicar can be assigned several non-leading positions in different pastoral offices at the same time according to can. 545 § 2. |

157 |

||||

|

It is possible for a priest to hold positions which exist on different constitutional levels as well according to the prescriptions of can. 554 § 1, since the legislator respects can 152 of the present CIC. The dean may hold on the one hand an officium as a pastor in one parochial office and an officium in the bishop's office according to which he exerts the duties of a dean. |

158 |

||||

However it is not possible for a pastor to hold more than one leading position in a single parochial office, i.e. it is impossible to transfer this leading position to the same person on the same level of constitutional law. A single person cannot carry out the duties of more than one leading position if this position is not split according to the duties it incorporates.13 This is why the legislator does not allow such a situation to arise according to can. 152. This is the reason why the leading positions have to be split i.e. the parochial offices have to be changed if one wants to achieve such an administrative construction. |

159 |

||||

|

Secondly, the legislator offers the possibility of splitting the leading position of a parochial office when there is a lack of priests or in other circumstances (on the background of can. 526 § 1, subset 2 and can. 515 § 2). Also the care of several neighboring (vicinus) parishes can be entrusted to the same pastor. According to J. Cleve this statement of can. 526 § 1, subset 2 is proof that every pastor can fulfill more or less all the duties and obligations with which he is entrusted. If this is not guaranteed positions cannot be granted cumulatively. When applying can. 526 § 1, subset 2 a diocesan bishop cannot violate can. 152. Therefore he must create appropriate conditions and structural changes which enable a reduction of duties due to the compatibility of positions.14 |

160 |

||||

|

Thirdly, it should be noted that the legal form of dividing the leading position in the parochial office is not mentioned explicitly by the Code of Canon Law. The legislator assumes it when he formulates can. 517 § 1. When circumstances require it, the pastoral care of a single parish or of different parishes together can be entrusted to several priests in solidum, i.e. together. However one of these priests has to be the moderator responsible for representing the parochial office in front of the bishop and to represent the parochial office in juridic affairs alone (can. 543 § 2, 3°). |

161 |

||||

|

One needs to discuss in another context to what extent it would have been necessary for the legislator to issue a plan of classification of duties before transferring the model of governing existent in can. 526 § 1, subset 1 upon the model of governing of can. 517 § 1. |

162 |

||||

|

|

|||||

III. The Design of the Legal Concept in can. 517 § 2 and in can. 533 § 1 |

|||||

|

The obligation of residence according to can. 533 § 1 draws attention to several presbyterial functions which can be described from a interdisciplinary and theological point of view with the sentence "The light is turned on in the pastor's house". |

163 |

||||

|

It is indispensable that every parish must have an individual nearby who is entrusted with the pastoral care of the parish and who works together with the leading pastor in fulfilling the cura pastoralis. This person administers all the duties which are entrusted to him or her based on her / his shared leading function in the parochial office. |

164 |

||||

|

One also needs to discuss in another context whether it is possible for a third person to hold a non-leading position in a parochial office including being in charge of all the duties of the parochial office when there are already two persons sharing a leading position. |

165 |

||||

|

If we consider a situation where the lack of priests in a diocese is so high that a pastor finds itself entrusted with 25 parishes, then this pastor has to be called aliquis sacerdos because he will be connected not just to only one parochial office but he will have to moderate the cura pastoralis paroeciae in 25 parishes. But since he shares his leading position in the pastoral office with a person who is not a priest, he has 25 colleagues in the parochial offices who are at the same time his co-workers and help him with the pastoral care. Or he has 25 colleagues with whom he shares the leading position which is again divided. From the point of view of employment law these colleagues have two supervisors who share the leading position in the parochial office. |

166 |

||||

|

Perhaps it is also possible to design the legal concept of can. 517 § 2 and can. 533 § 1 in a different manner. For example, the leading position could be divided between three persons or a person who is not a priest could be assigned several leading positions in different parochial offices like the priest. In any case, the diocesan bishop has always to ensure that all duties of the pastoral office are met, including the duty of residency, as all duties of the pastoral office are to be complied with rite apteque according to can. 533 § 1. |

167 |

||||

If the individual person who is endowed with the performance of parochial functions according to can. 533 § 1 should be a parochial or pastoral assistant or a permanent deacon or could also be a layperson who has not studied theology but possesses enough theological knowledge to enable him to perform these duties, should be discussed from a theological point of view and from the perspective of long-term financial consequences for a diocese. |

168 |

||||

|

If one can say that a person "governs the parish" when a pastor does not live in the rectory near the church and another person must be entrusted with fulfilling the parochial functions according to can. 533 § 1, could be examined from a canonistic point of view. It seems that laypeople15 can govern a parish in this sense. |

169 |

||||

|

With all reflections on regimen paroeciae in the time of shortage of priests it is decisive that all the functions listed by the legislator in can. 533 § 1 are fulfilled for the sake of the members of the parish. |

170 |

||||

|

|

|||||

D. Conclusion and Relevance of the Thesis |

|||||

I. Methodological Questions |

|||||

|

The present reflections offer a background of legal theory which helps one to understand canon law as a theological discipline by the application of a juridical method. In this way one can reflect in a more appropriate manner the essence and the self-awareness of the christians who belong to the moral person Catholic Church as defined in can. 113 § 1 and especially in can. 368. |

171 |

||||

|

The present reflections are not made from a dogmatic background. Still dogmatic assessments are introduced in the reflections since canon law is a theological discipline. The legislator's affirmation that the priestly consecration is needed for the spending of the sacrament of anointment (can. 1003) or for the holding of homily (can. 767 § 1) has a dogmatic background. Therefore this background is necessary for a canonistic analysis. |

172 |

||||

|

From the perspective of methodology I apply a scientific interdisciplinary dialogue, which is often used in theology16. My point of reference is the general administration law. |

173 |

||||

|

My reflections are done from a positive-legal perspective, which is made clear by the interpretation of can. 517 § 2 done by the legislator. He only talks summarily about the tasks of the cura pastoralis. Some duties of a parish priest can be taken over by non-priests by respecting the law and the dogmatic rules of the church (like in can. 519). The universal legislator leaves to the legislator of the particular church a free hand in describing the governing function of the parochial office. |

174 |

||||

|

The legislator wants to insure by can. 517 § 2 that a cleric governs and directs the cura pastoralis of a parochial office and insures herewith the spiritual dimension of the church by his pastoral care. |

175 |

||||

|

|

|||||

II. Summary of the Main Epistemological Ideas of the Paper |

|||||

|

Within the present canonistic discussion which is dogmatically influenced |

176 |

||||

|

177 |

||||

|

178 |

||||

|

179 |

||||

|

180 |

||||

|

181 |

||||

|

182 |

||||

|

On the basis of a comprised presentation of the canonical reflection done on a dogmatic background one can affirm that conclusive results can be aimed at if one applies the General Administration Law and a clearly specified vocabulary. |

183 |

||||

|

The already used canonical notion of office can be extended to the notion position in an altered version, and be understood as an institution of law founded within the parochial office but developed from the perspective of an hierarchy of positions. The "office" carrying the meaning consecration is perceived as task oriented. The parochial office is to be seen as a legal institute which is erected because of the parish. Within the parochial office the legislator designs the spheres of activity of the parish and creates several positions which have to be occupied. |

184 |

||||

|

This essay provides a legal theoretical basis for the application of the guidelines "Pastorale Ansprechperson" (Pastoral Contact Person) which has been elaborated in the diocese Rottenburg-Stuttgart.17 The new conception I presented goes beyond these guidelines, as the laypeople who are active in pastoral activities and the permanent deacons already enjoy the status of a juridical person permissible by the Code of Canon Law due to the shortage of priests. It would be important that their status would also be recognized by the legislator of particular law since there is sufficient legal foundation in the Code of Canon Law based on a theological dogmatic content of the Magisterium of the Church which would enable them to take over these responsabilities. |

185 |

||||

|

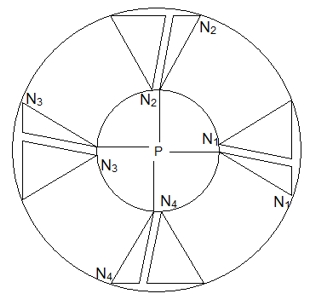

In analogy with graph 3 and 4 and under the presupposition that the duty cura pastoralis of the circle of activity of four parishes has to be lead by one single pastor, I have illustrated my thesis in the following schemes: |

186 |

||||

|

187 |

||||

|

Four parishes are united into a pastoral unity (in Germany known as Verbund or Seelsorgeeinheit). This is illustrated by the outer circle. The parochial offices of these four parishes are changed in as much as every leading position is divided according to its specific activities. |

188 |

||||

|

The respective smaller triangle on the left signifies the split leading position of the pastor, the smaller triangle on the right the divided leading position of the non-pastor. |

189 |

||||

In the inner circle one can find the persons who are colleagues, in the outward circle one can find the co-workers of the persons holding the divided leading positions in the parochial office. |

190 |

||||

|

Graph 5 describes the situation that the pastor has four colleagues who are not priests but who are at the same time his cooperators for the fulfillment of the cura pastoralis. In graph 6 the pastor has four times a colleague who is not a priest (N1-4). For every parish the pastor and his colleagues have the same pastoral cooperators (Na-d). |

191 |

||||

|

The cooperator of the pastor who is not a priest takes over the duties of the cura pastoralis for which a sacramental ordination is not required from a dogmatic point of view (graph 5 and 6). |

192 |

||||

|

The colleague of the pastor who is not a priest (N1-4) and / or the non-priestly cooperator of the pastor and of his non-priestly colleague (Na-d in graph 6) takes over the residence requirement in the parish for which the pastoral office was erected which is stipulated by the legislator. |

193 |

1 The present essay is based on the monograph of E. M. Morein, Officium ecclesiasticum et universitas personarum. Bestimmung des Rechtsinstituts Amt, Berlin 2006, 43-96 and 193-195.

2 J. Ipsen, Allgemeines Verwaltungsrecht, Köln, Berlin, Bonn, München 32003, Notes. 215-218.

3 E. M. Morein, Officium ecclesiasticum et universitas personarum. Bestimmung des Rechtsinstituts Amt, Berlin 2006, 193.

4 See: E. M. Morein, Officium ecclesiasticum et universitas personarum. Bestimmung des Rechtsinstituts Amt, Berlin 2006, 127-192.

5 For a commentary on can. 148 see. E. M. Morein, Officium ecclesiasticum et universitas personarum. Bestimmung des Rechtsinstituts Amt, Berlin 2006, 370.

6 It becomes clear that H. Socha uses the canonistic concept office but refers to a position. On the background of a new set of criteria emerging from the terminology of legal administration we assumed in our analysis that the legislator made a distinction between the two concepts - "office" and "position" in an "office" - when using the concept officium ecclesiasticum in can. 148, subsets 1 and 2.

7 Compare R. Köstler, Wörterbuch zum Codex Iuris Canonici, München und Kempten 1927, 102.

8 Compare the statement of the German Bishops: "Zum gemeinsamen Dienst berufen. Die Leitung gottesdienstlicher Feiern. Rahmenordnung für die Zusammenarbeit von Priestern, Diakonen und Laien im Bereich der Liturgie", Bonn 1999.

9 Cf. E. M. Morein, Officium ecclesiasticum et universitas personarum. Bestimmung des Rechtsinstituts Amt, Berlin 2006, 295-338 and 343.

10 Cf. H. Schmitz, Officium animarum curam secumferens. Zum Begriff des seelsorgerischen Amtes, in: Ministerium iustitiae. FS für H. Heinemann, eds. A. Gabriels, H. J. F. Reinhardt, Essen 1985, 127-137, 128.

11 Cf. H. Schmitz, Officium animarum curam secumferens. Zum Begriff des seelsorgerischen Amtes, in: Ministerium iustitiae. FS für H. Heinemann, eds. A. Gabriels und H. J. F. Reinhardt, Essen 1985, 127-137, 130.

12 It is important to check whether the legal texts of the concordats also make a reference to the situation of lack of priests and which is the exact meaning of the concept "pastor" (Pfarrer) in the concordats. Does the concordat mean the holder of the non-divided leading "position" in the parochial "office" or does it mean the administrator of the representative body "pastor" (Pfarrer). The administrator of this body could also be a non-priest because the persons acting in the body are not expected to fulfill duties which require sacramental ordination, as it is prescribed dogmatically by the Code.

13 Cf. J. Cleve, Inkompatibilität und Kumulationsverbot. Eine Untersuchung zu c. 152 CIC/1983, Frankfurt am Main 1999, 33.

14 Cf. J. Cleve, Inkompatibilität und Kumulationsverbot. Eine Untersuchung zu c. 152 CIC/1983, Frankfurt am Main 1999, 250-256.

15 Cf. L. Schick, in: Handbuch des katholischen Kirchenrechts, Regensburg 21999, 493.

16 R. Reck, Kommunikation und Gemeindeaufbau, Stuttgart 1991. The author has analyzed in his doctoral thesis the Pauline Epistles from the point of view of modern communication science. He also applied in his analysis a scientific-interdisciplinary dialogue.

17 Pastorale Ansprechperson, Ed.: Bischöfliches Ordinariat, Hauptabteilung V, Rottenburg 22009.